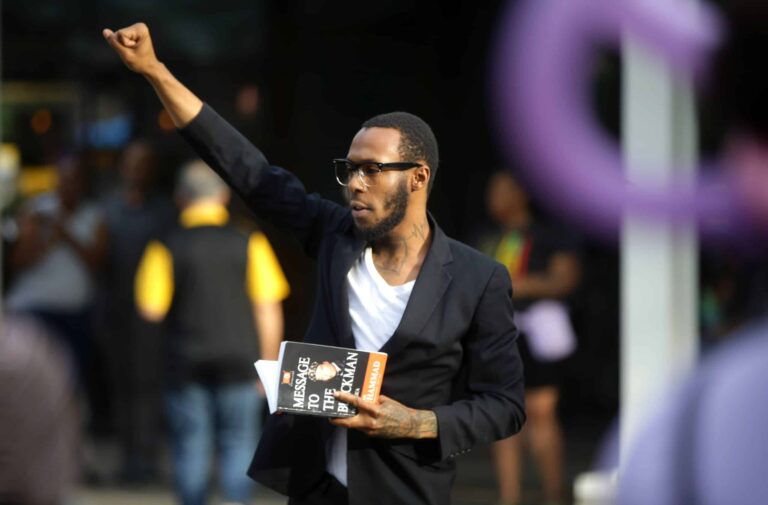

Although mentioning the Black Panthers or the Black Panther Party makes many nervous or uncomfortable, including causing many to swallow their own saliva to recover from the uneasiness that accompanies such mentioning, just as many of you did when you read this article’s headline, much of what elicits that response is a byproduct of ignorance about them, the party, and its platform.

One of the best ways to gain a foundational understanding of the Black Panther Party is to assess the ten-point program in its 1966 platform. While the Black Panthers were considered radicals, and they needed to be radicals to oppose a racist and white supremacist system committed to denying them equity, justice, liberty, and humanity, what they expressed in the platform shouldn’t have had to be viewed as radical.

Since not enough people have read the Black Panther Party’s platform, again, written in 1966, it’s vital to offer folks an understanding of what it says and why it states what it does. Time and space limitations don’t allow the present writer to address each point. However, this piece discusses the platform’s core economic agenda to evidence its productive Black radicalism and champion this radicalism to combat racial capitalism’s economic exploitation.

Black Panthers on Employment

With its ten-point program, the Black Panther Party (BPP) platform states, “We want full employment for our people.” Capitalism demands that people have an adequate amount of money to survive. Without a job, even “a Black job,” to invoke the racially ambiguous phrasing—and that’s being kind—of former President Donald Trump, no one, including no Black, can survive in capitalist America. For the Black Panthers to insist that all Blacks have the means to secure their survival isn’t radical; it’s a humane demand.

These Black radicals, radical because they needed to be, were serious about making government work for them. In the BPP platform, they declared, “We believe that the federal government is responsible and obligated to give every man employment or a guaranteed income.” This platform was written immediately after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Therefore, it’s essential to recognize that the previous sentence offers some crucial context for the Black Panthers’ demand for government to guarantee everyone a job or income.

The BPP platform’s position on employment is part of a long and bloody struggle to force government to give civil and voting rights to everyone, especially Blacks, given that no group in America has suffered from the ingrained history of racism, discrimination, and white supremacy as deeply and consequentially as them. During 1966, therefore, Blacks were subjected to dehumanizing conditions, conditions so extreme, so malevolent, that the racists responsible for such conditions had to be coerced into giving Blacks these rights.

These God-given civil and voting rights guaranteed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had to be created and enacted to force racist whites and a racist and white supremacist system to extend these most basic rights to Blacks. Therefore, the Black Panthers’ demand for guaranteed income or employment was an effort to fight vigorously against the economic exploitation Blacks had been enduring since their forced arrival on the land White colonizers stole from the Native Americans.

Necessary Black Resistance

Instead of submitting to White racists’ intentions for them to die, which is the purpose of this economic exploitation, Black Panthers heeded the clarion call of the most potent Black resistance poem in American history, “If We Must Die,” penned by Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay in 1919. In “If We Must Die,” McKay challenged Blacks to resist White racists’ plans to murder them by calling all Blacks to wage war against their racist oppressors through Black solidarity, deeming such solidarity and resistance as “noble.”

For McKay, if Blacks were to die at the hands of racist Whites, they shouldn’t accept this death willingly, as if they’re docile bodies. Quite the contrary, if they were to die, it should be while fighting back. In a similar vein, Dr. Cornel West, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Professor of Philosophy and Christian Practice at Union Theological Seminary in New York and a towering Black public intellectual and civil and human rights activist committed to love, truth, and justice, contends that Blacks, at their best, have always evinced “black fightback,” a willingness to resist racism and white supremacy, never permitting them to have the last word.

The Black Panthers, who shared this revolutionary spirit of McKay and who participated in the best of the black radical tradition, refused to sit back and die at the murderous hands of racists and white supremacists. The Black Panthers were determined to make the promises of equality and democratic freedom beautifully articulated in the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution manifest themselves in practice for everyone, including formerly enslaved Blacks.

Poverty in 2024

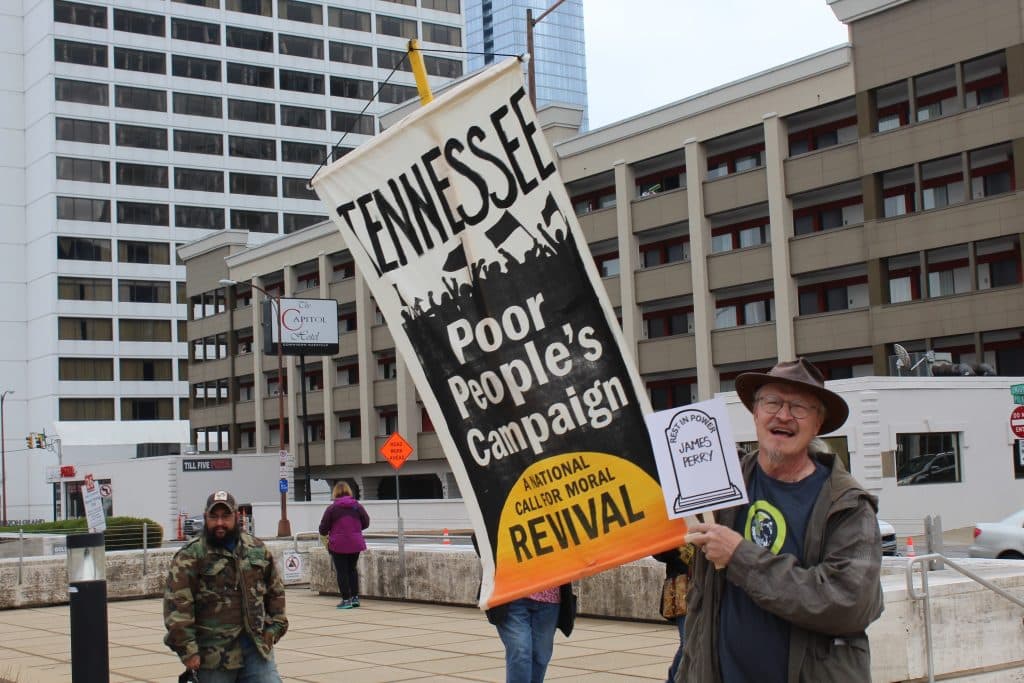

According to the United States Census Bureau, 11.1% of the American population and 17.9% of Blacks suffer from poverty, meaning well over 30 million Americans confront poverty. Who will champion the poor? Although our dear sister Kamala Harris is promulgating some details of her “opportunity economy” agenda, and some of its provisions will support the poor, she, like most elected officials, focuses primarily on “the middle class,” neglecting the poor. The poor need a targeted and comprehensive agenda.

Unfortunately, what Harris is advancing isn’t the agenda the poor need, although, to be clear, it’s far better than Trump’s “concepts of a plan.” Also, to be fair to Harris, as the Black Panthers desired, she communicated she wants to “build an economy where everyone is working” during an interview with Stephanie Ruhle on MSNBC.

The onus of an anti-poverty agenda isn’t solely on Vice President Harris. Black solidarity is needed to lead an organic citizens’ movement for economic justice. For economic justice to become a national priority, and it should sooner rather than later, Black solidarity must lead to broad, diverse coalitions across the nation committed to eradicating poverty.

Reverend Dr. William J. Barber, II, arguably the most vocal and passionate advocate for the poor in America, has supplied us with a national platform, the Poor People’s Campaign, to champion the cause of the poor. For Barber, America’s unwillingness to end poverty in this nation, for which it has the economic capacity to do it, is not simply a matter of policy and economics; it’s a moral failing, in his estimation.

Final Thoughts

Dr. Barber is right: America’s refusal to end poverty is a moral failing. In Can You Hear Me Now?: The Inspiration, Wisdom, and Insight of Michael Eric Dyson, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, leading public intellectual, University Distinguished Professor of African American and Diaspora Studies, and University Distinguished Professor of Ethics and Society in the Divinity School at Vanderbilt University, posits, “People who give money to the poor deserve praise; people who give their lives to the poor deserve honor.”

Without question, Dr. Barber’s tireless economic justice work merits him “praise” and “honor.” If more people joined his work, we could compel local, state, and national elected officials to develop and enact policies to eliminate poverty in America. Also, in the previously mentioned work, Dr. Dyson asserted, “The poor are, in effect, socially dead persons.” While this is true, what is equally valid is they will be physically dead if we don’t mandate our elected officials to officials to liberate them from poverty.

If the Black Panthers’ insistence on having a moral and ethical government that ensures everyone has a job or guaranteed income is radical, then we all need to be radical. We have the means to rid this nation of the rot of poverty. However, this is the pressing question: Do we have the moral will and political courage to end poverty in America?